Research into teamwork has frequently identified communication as a key factor affecting success, especially when team members are from diverse backgrounds. Two issues are frequently mentioned: discrepancies in language proficiency and ‘silent’ members who contribute little to group discussions. Blame for these ‘problems’ is typically heaped on the individual(s) concerned, but it’s important to ask how fair this is. A relatively recent longitudinal study offers some fascinating insights.[1]

The Study

Carolin Debray worked with a group of MBA professionals who were conducting project-based teamwork during their year of study. She followed one particular team over a course of 8 months, observing and audio recording their meetings. The team members came from 5 different countries: UK (David), India (Jay and Akshya), Germany/Italy (Bruno), China (Alden) and Nigeria (Bev)[2].

As part of the MBA program, they were given a team training session at the start of their collaboration, and this was followed by further regular team training and review sessions, guided by a facilitator.

All team members had a minimum of 5 years working experience, with most of them having experience of multinational teamwork in international workplaces. All of them had different functional expertise and had worked in different sectors, such as accounting, marketing, sales etc. Four of them, David, Jay, Akshya and Bev, had all received their education in English and were highly fluent in the English language. Alden and Bruno were less fluent in English but had nevertheless achieved the high standard required for entry to the degree program.

Participation across the project

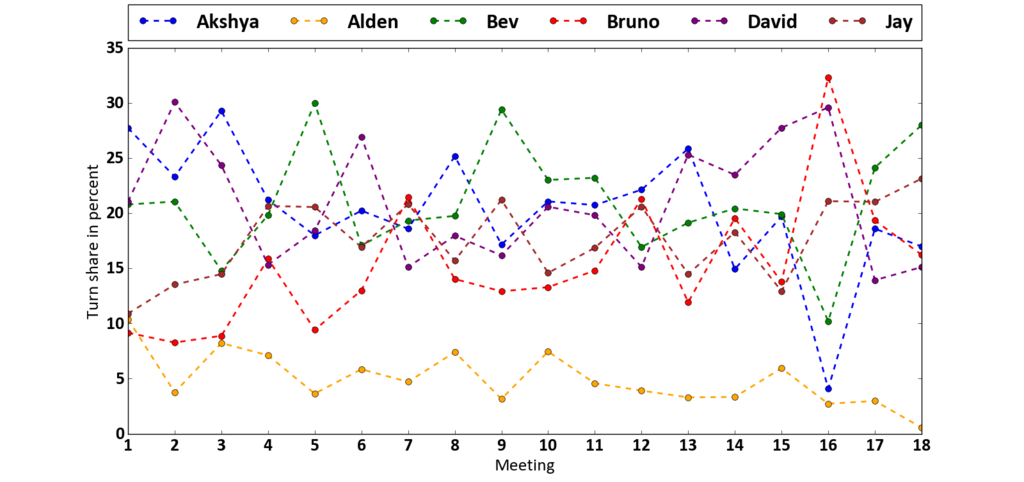

Debray first explored the proportion of speaking turns taken by each team member over the course of the 8 months of teamwork. The figure below shows what she found.

As can be seen, at the very first meeting, three people (Akshya, David and Bev) spoke proportionately much more than Jay, Bruno and Alden. However, by the third meeting, Jay was participating more, and by the fourth meeting, so was Bruno. Alden, however, remained a minimal contributer across all the meetings, with the proportion of his speaking turns reducing if anything, especially in the second half of the project. In other words, five out of the six team members shared the majority of the talking in the project meetings, with Alden contributing very little.

What then caused this? Was it his ‘fault’ or were other team members at least partly responsible? Debray analysed the audio recordings to find answers to this question.

Team members’ comments and attitudes

One set of insights can be found from the comments and attitudes that team members expressed. These sometimes occurred during their review sessions with the facilitator, with everyone present, and sometimes during their team meetings. Some examples are as follows:

Alden is ‘silent’

When asked by the facilitator for comments about their teamworking, both Akshya and Bev maintained “they never talk, Alden Bruno”. Bruno immediately denied this, saying “That’s not true”. Both men also pointed out that the others were partly responsible for the problem – that others often spoke too fast, used slang terms, and didn’t take the time to listen or to explain things properly.

Alden is ‘different’

Bev maintained that she cannot meet the “real Alden – I feel like I need to keep on dragging something out of him.” Bruno stood up for Alden, but the team continued to talk about him as though he wasn’t present. By doing this – by talking about him rather than with him – they effectively excluded him from the conversation.

Alden is ‘really Chinese’

In their meetings, team members sometimes told Alden that he was “really Chinese”, and made comments like “I know he is from a shy culture but … (sigh).” In other words, they stereotyped him.

Team meeting dynamics

These negative perspectives on Alden were also reflected in the dynamics of the team meetings:

- Members often talked over Alden

- They often interrupted him

- They regularly displayed only token interest in what he said

- They regularly positioned him as an outsider by talking about him in the third person (i.e. using he or him), as if he was not in the room

They sometimes dismissed what he said; for instance, once when he made a suggestion, Bev responded by saying “Oh please … go away.”

The Consequences for Alden

Alden repeatedly tried to counteract all the above attitudes and positionings, but they were so intertwined that it was virtually impossible for him to do so. The behaviour of the other team members interacted to co-construct him and position him in all those negative ways – as silent, different, and incompetent; in other words, as not a real team member but as someone the five of them needed to carry.

Key Takeaways

Inclusion or exclusion of team members results from the dynamics of team relations and interactions:

- Team members who are (initially) less proficient in English are at risk of being marginalised by the more proficient members;

- They may be positioned as different, problematic, and incompetent, irrespective of their level of expertise;

- Stereotyping often exacerbates these negative positionings;

- Their ideas are often silenced interactionally, thereby excluding them from contributing to the tasks;

- Repetition of the above perpetuates the negative positionings and prevents the member from repositioning him/herself.

In other words, it is too simplistic to treat ‘being silent’ as the ‘fault’ of an individual. Nor is it necessarily a function of low levels of psychological safety, as traditionally conceptualised. Rather, communication – as with dancing – is a collaborative enterprise, with everyone’s behaviour impacting dynamically on the behaviour of others and thereby affecting the overall functioning and achievement of the team. Every team member, individually and collaboratively, thus plays a role in promoting or undermining inclusion. Teams need to work hard at co-ordinating their interactions for the maximum benefit of each person and of the project.

Global fitness in communicating in teams

If you would like to learn more about communication in teamwork, including ways of promoting co-ordination and inclusion, get in touch with us. We offer a range of services to support you in this. Just email GPC or Helen directly.

Also, our latest book Global Fitness for Global People: How to manage and leverage cultural diversity at work provides many insights.

Professor Helen Spencer-Oatey, Managing Director

References / Notes

[1] Debray, C., & Spencer-Oatey, H. (2019). ‘On the same page?’ Marginalisation and positioning practices in intercultural teams. Journal of Pragmatics, 144, 15–28. Available open access here.

[2] All names of team members have been changed.