This post is the second of a three part series on Context and Culture

Part 2: The communication setting – key components

In our GPC Insight, Context and Culture Part 1, we introduced the notion of the communication setting (more technically known as the interactional context) and considered one of its important features: the participants.

In this Part 2 of the series, we present a framework for understanding the key features of the interactional context as a whole. Communication always takes place in a particular setting, such as where it takes place (e.g. its physical location), when it takes place (e.g. time of day or on what kind of occasion), and the people present (i.e. the participants, as well as any people nearby who may overhear the conversation). Many of these features can be summarised into the notion of a communicative activity – a communication event, such as a business meeting, a sales encounter, or a university seminar/workshop, that is recognised by others as having a set of familiar features.

First consider the following case study.

I was the programme manager for a Sino-British set of educational projects, known as eChina-UK, and in the second year of the programme, we arranged a workshop in Beijing for the British and Chinese teams. The purpose was for the team members to share with each other what they had achieved so far, give each other feedback on what had been done, and to plan next steps. A similar workshop had been held very successfully in the first year of the programme in the UK.

When we arrived at the location in Beijing where the workshop would take place, the British team members were shocked. The room was formally laid out with a very large U-shape of mahogany tables that could not be moved, with a podium at the front with a microphone, and with a massive number of flowering plants in large pots that surrounded the podium and filled much of the gap in the U-shape. One of the British project managers exclaimed: ‘How can we discuss our projects in a room like this? We need to have small, moveable tables.’ Our Chinese hosts responded that this would not be possible and that this was the best arrangement for a workshop in China.

Understanding the notion of a communicative activity – a key framework for understanding the interactional context – is crucial for gaining insights into collaboration challenges such as this. Here I draw on Jens Allwood’s conceptual framework (pp.6-7) of communicative activities.

1. The purpose of the communicative activity

Firstly, all communicative activities have purposes associated with them. However, not everyone will necessarily agree on what those purposes are. In this particular case study, the British team members saw the primary purpose as being small group discussion and feedback, so that the project goals could be achieved more effectively. The Chinese team members, on the other hand, reported later that they wanted to demonstrate to their leaders the importance of the collaborative project and how successful it had been so far.

2. Procedures for carrying out the communicative activity

The purpose of the communicative activity is often (but not always) closely linked with the procedures for carrying it out. In this particular case study, the British team’s goals for the event required small group discussion, while for the Chinese it meant formal presentations. In fact, it is common for there to be cultural differences over the expected procedures for carrying out a communicative activity.

- If you’d like to learn more about this, ask us about a guest talk or masterclass session. Just email GPC or Helen directly.

- To learn more about handling cultural diversity at work more successfully, and to access a wide range of case studies, activities and tools, see our 2022 book Global Fitness for Global People: How to manage and leverage cultural diversity at work.

3. Role responsibilities for carrying out a communicative activity

Closely linked with the procedures for carrying out a communicative activity are participants’ role responsibilities for doing so. Consider the following incidents, also connected with the eChina-UK programme.

Incident 1

During a visit to Beijing, a UK technical specialist and I met with a senior member of the Chinese Ministry of Education (MoE) to discuss some technical matters associated with the e-learning projects. The MoE member of staff was speaking at length about a particular issue, so that an interactive discussion was impossible. At one point, the technical specialist interrupted her and asked if he could ask a question. People in the room looked shocked, and he was simply told ‘No.’ He was expected to wait until she had finished speaking (however long that took). He, on the other hand, was expecting to have a ‘to-and-fro’ discussion.

Incident 2

One of the Chinese project teams had been visiting their UK counterpart team for some detailed planning. As the overall programme manager, I attended some of their meetings – all of which were very informal. At the end of the visit, we all thanked each other and said farewell. The Chinese team leader then came up to tell me that, in my role as programme manager, I should have made a formal speech at the end of the visit.

In Incident 1, much of the issue was associated with the ‘appropriate procedures’ for carrying out a meeting with a government official. However, there were also some role responsibility issues. The technical specialist was seen as having lower status than me, and thus not entitled to take the initiative to ask a question. If I had done so, it would have still been a breach of protocol, but would have been somewhat more acceptable. In Incident 2, the Chinese team leader felt that my failure to give a formal speech at the end of their visit was a failure to fulfil my responsibilities as programme manager – that my omission had detracted from the success of the visit and my appreciation of what the teams had achieved. As GPC Insight, Context and Culture Part 1, has explained, cultural factors can have a major impact on people’s conceptions of role responsibilities. Thinking about it from a communicative activity perspective, can offer richer insights.

- If you’d like to learn more about this, ask us about a guest talk or masterclass session. Just email GPC or Helen directly.

- To learn more about handling cultural diversity at work more successfully, and to access a wide range of case studies, activities and tools, see our 2022 book Global Fitness for Global People: How to manage and leverage cultural diversity at work.

4. The setting for carrying out a communicative activity

Also closely intertwined with purpose, procedures, and roles, is the setting in which the communicative activity takes place. This can include a number of things, such as:

- Whether the activity is face-to-face or online.

- Where the activity takes place; e.g.

- In which country / countries

- In what type of building (e.g. shop, open plan office, company boardroom)

- What tools and artifacts (e.g. furniture & seating arrangements, computers) are present and /or required.

We noted in the first case study above that the furniture in the room was integrally connected with the purpose of the event. It affected the way it supported (or hindered) the procedures and whether the purpose could easily be achieved. Setting is always an important element of a communication activity but can be greatly influenced by cultural factors.

- If you’d like to learn more about this, ask us about a guest talk or masterclass session. Just email GPC or Helen directly.

- To learn more about handling cultural diversity at work more successfully, and to access a wide range of case studies, activities and tools, see our 2022 book Global Fitness for Global People: How to manage and leverage cultural diversity at work.

Points to reflect on

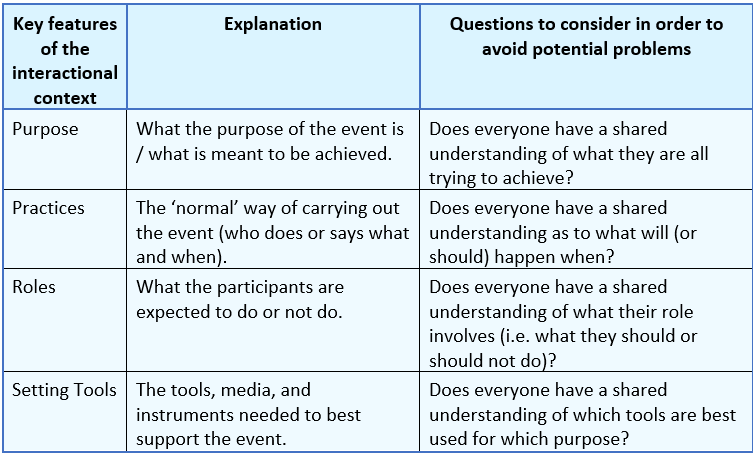

These two GPC Insights, Context and Culture Parts 1 and 2, have both focused on the interactional context. All the features we have considered can easily be influenced by cultural factors, so it is important to check on your and others’ expectations and understandings of the various elements. You can use the table below to help you consider the communicative activities you’re involved in and to reflect on the key features of the interactional contexts where different participants might have varying conceptions.

The third and final GPC Insight on this topic, Context and Culture Part 3, focuses on other levels of context (i.e. beyond the interactional context) and how culture impacts all the levels in an interconnected and dynamic way. To make sure you don’t miss it, along with other GPC Insights, follow GPC on LinkedIn.

- If you’d like to learn more about this, ask us about a guest talk or masterclass session. Just email GPC or Helen directly.

- To learn more about handling cultural diversity at work more successfully, and to access a wide range of case studies, activities and tools, see our 2022 book Global Fitness for Global People: How to manage and leverage cultural diversity at work.

Professor Helen Spencer-Oatey